(16 min read)

Questions about video gaming are among the most frequent I receive. It’s something that really worries parents. But they could actually save your life.

Before you had children you swore you’d never do it. But we all succumb in the end (except for those morally superior parents – I applaud you). You’re in a restaurant, the food is taking ages to arrive, you’ve got your parents-in-law or friends with you and your children start to fidget and wriggle, then whinge and bicker. You’ve already said “they’re not usually like this!” with a cheery smile, you’ve whispered in their ear that you’ll give them Haribo as a treat if they can sit nicely for a few more minutes; you’ve taken them off to the loo as an excuse to stretch legs, and now you’ve exhausted all options. It’s tears or Angry Birds; a meltdown or Minecraft. The first time I took our 10 day-old baby out with her sister and brother on my own, I bribed them with Fruit Ninja if they sat nicely whilst I fed the baby. A lady came over to congratulate me on the wonderful behaviour of all three, not realising my phone was resting behind the menu. We all smiled like The Waltons. I was proud. And we pretended the phone wasn’t there.

So, will video games make our children aggressive and unsociable?

Well, it depends. One study will tell you video games can help our children to learn; another will suggest that it could make them angry. The more I read, the more I subscribe to the belief that video games can benefit your child and even be used to change the world for the better (and stick with me on this one- more in another article).

Yes, there are violent and distasteful games, which have the potential to distort our children’s brains for the worse, but used correctly, and sensibly, I’m afraid I will probably take your child’s side in the argument; there are many desirable benefits. As long as video games are played for reasonable amounts of time and are interspersed with time outdoors and playing with actual toys, it is likely that you child will benefit from them.

There are millions of different video games from hundreds of distinct genres and sub-genres, which can be played on computers, phones, consoles, hand-held devices and laptops, once a week or several hours a day. The term ‘video game’ is not a single ‘thing’ and so it’s hard to make general conclusions in scientific research – to know what effect it is having on your child’s brain, you need to define exactly what type of game you mean and also for how long they’re playing it for. It’s a bit like asking what the effect of food is on the body. It depends.

What is certain, is that games are an inevitable part of children’s lives, and, statistically, probably yours too. More than 90% of school children in the UK and the US play video games. But the average age of a gamer is, in fact, around 30 years old. It’s us that are playing them into the night, when the kids are in bed. (Or maybe chess, if you’ve watched The Queen’s Gambit.) In the UK, the number of school children who have played any sort of video games is around 99% – they’re just so easy to play on a parent’s phone (in fact, it’s us parents who hand them to children, to buy five minutes’ precious peace to get through the supermarket checkout).

In January 2020 it was estimated that there were more than 3billion video gamers in the world. To put it into perspective, that’s way, way, more than double the population of Africa. More like two Africas, and the USA, plus Thailand. All playing games.

What do parents say?

Speak to parents and you’re probably in the same boat: argue over time spent playing; battle over 15-rated games when your child is 13 (all their other friends regularly play 18-rated games, apparently); the constant plugging-in of ear phones, even on the once-in-a-lifetime safari holiday in Kenya; worries over addiction; and grumpiness that accompanies bouts of gaming. Plus, parents worry about the fact that they know far less about gaming than their children.

Children are universally creative in flouting rules: the ‘no phones in bedroom’ trick of leaving an empty phone-case next to the charger to use the phone under the duvet for hours. Sound familiar?

What does the research say?

There have been many studies into the effects of ‘action video games’ on the brain. Is running around a virtual Alcatraz using lasers to exterminate zombies in ‘Call of Duty’ harming your child? Or are they learning how to work as a team, and to deal with losing and winning? Are their brains being trained to become super-efficient at identifying and reacting to visual stimuli? Well, all of it actually, but it really does depend.

Brains are plastic. That is, they alter the ways the neurons are wired together, in the light of new experiences. The more we practice these new experiences, the stronger and more efficient these connections become, until eventually we turn into experts. Whilst reading this, your brain no longer has to sound out the phonics of each letter like you did as a young child– it has wired itself to recognise whole-words and read faster than conversation speed. Which is handy.

When your child plays an action video game, they are rewarded for quick, accurate judgements and good hand-eye coordination. Players with the best focus, the speediest responses and largest working memories score highest. So, as long as your child keeps playing, it would be surprising if the brain didn’t make corresponding neurological changes to support these behaviours.

And there is a considerable body of research proving that playing action video games does enhance a wide range of behaviours, including faster visual processing speeds, better low-level vision, improved attentional control and increased working memory spans. The benefits from playing the game are a direct reflection of the skills required to play the game well.

I have been lucky enough to meet Professor Daphne Bavelier twice. She is a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Geneva and one of the leading lights in the world of action video game research. Her current lab is producing fascinating findings that defy all popular beliefs about video gaming being the harmful hobby of social recluses.

When Professor Bavelier talks, she invites us to abandon our preconceptions, and to “step into the lab and measure, directly, in a quantitative fashion, the impact of video games on the brain”. Bavelier says, “I’m going to argue that, in reasonable doses, those action-packed shooter games have quite powerful and positive effects on many different aspects of our behaviour”.

So, what are these positive effects? Let’s start with the physical. Your eyesight can improve. Action video gamers actually have better eyesight than those that don’t play, in two different ways: firstly, they can resolve fine detail better (so are less likely to need reading glasses) and secondly, they have better contrast sensitivity and can detect more subtle shades of grey. Bavelier says this could make the difference between having an accident and not having an accident when driving in fog, for instance.Yes, it could actually save your life.

Also, in patients with amblyopia, or ‘lazy eye’ (when the eye and the brain don’t work together properly), playing action video games can improve visual acuity. Traditionally, treatment involved placing a patch over the good eye, in order to force the ‘lazy’ eye to do some heavy lifting – meanwhile the poor child has to put up with walking round wearing an actual eye-patch. However, the dominant eye remains unused, so the eyes don’t learn to work together. In any event, only around half of amblyopic children with patched eyes achieve normal vision. But researchers have developed a far more appealing treatment: at the Retina Foundation in Texas they get children to play computer games whilst wearing special glasses with different coloured lenses. The amblyopic eye can only see high-contrast red pictures and the normal eye low-contrast blue[i]. When the images overlay, they form binocular perception and eventually, through repetition, the eyes and brain learn to communicate better.

The computer-gaming group was seen to have more than double the improvement than the patched group. (And what happened to those poor patched children? After two weeks they switched to game playing and by the fourth week had made visual gains that matched the original game play group. Phew). The key factor, according to the researchers, was the high rate of compliance in the treatment: the children genuinely enjoyed playing the game. If given the choice in treatments, wouldn’t you?

A screenshot of ‘Dig Rush’. The amblyopic eye can only see high-contrast red, the normal eye only sees low-contrast blue whilst both eyes see grey background elements. Credit: Retina Foundation of the Southwest.

Ok, so what about the familiar despondent cry from parents that video gaming leads to attention problems, and greater distractibility? Well. Back to Bavelier’s talk. She invites us to play a game from her lab: calling out the colour of the ink used to write words for colour – so the word ‘red’ might be written in blue ink, and the word ‘yellow’ in green. It starts off easy. In a room full of academics, there is an air of smug confidence. But as the speed increases, and our brains grow fatigued, it becomes increasingly challenging.

The reason it’s challenging is because of the cognitive conflict between the colour of the ink and the word itself. The better your attention, the quicker you are able to resolve this conflict and shout out the correct word. Younger people are better than older people. And, yes, people who play a lot of action video games resolve this conflict faster than the average person.

How fast you can say the colour of the ink rather than the spelled word is an indicator of your attentional control.

In another test, Bavelier gets us to watch a group of images of smiley yellow faces and a few blue faces darting around inside a large circle. After a few seconds, the blue faces turn yellow and some of the yellow ones turn blue. We have to state the original colour of a random face. It’s harder than it sounds – “if you move your eyes you are doomed”, Bavelier tells us. Most adults can track between 3-4 objects. But, an action video gamer can track between 6-7 items.

There’s more. In her lab, Bavelier has also shown that action video gamers are experts at multitasking, which is the ability to switch rapidly between tasks (no one, not even working mothers of several children, can actually concentrate consciously on two tasks simultaneously). Non-gamers, who listen to music, chat on several messenger groups and research their homework (sound familiar?) may argue that they’re good at multitasking. They are not.

Non-gamers who engage in this sort of multimedia tasking are, in Bavelier’s words, “abysmal” at switching rapidly between the lab tasks – they demonstrate a greater time lag.

But perhaps it’s just that people who have quick reactions and really good working memory are more drawn to playing action video games. After all, the games require these skills, so if you already have them you’re more likely to be successful, right?

Wrong.

This is the crux of Bavelier’s work: to discover what happens to the brains of non-gamers when they play. Which parts of gaming contribute to better learning, vision and attention?

To test this, and to establish causality, she isn’t interested in people who are already gamers, but rather people who don’t play video games.

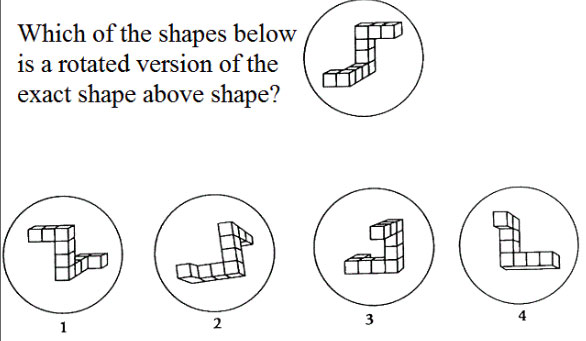

Her lab participants are (in her words) “forced” to play 10 hours of video games in a week, and then sit mental rotation tests after gaming. The results? They performed better. Even more interesting is that this benefit persists for months, even if they stop playing.

When participants with no previous game-playing experience played games, their ability to mentally rotate objects improved.

This Christmas (2020) my husband and I bit the bullet and bought our children a Nintendo Switch … So here we go!

___________________________

PS: We’re now halfway into lockdown January 2021. Do we have enhanced hand-eye coordination and speedier visual processing? Who knows. Are we having a huge amounts of family fun along the way? Absolutely. We still go outside each afternoon, we still eat together and no one has become obsessed. And on these early winter evenings, it’s rather brilliant. (And some of us are even learning to be better losers.)

[i] Kelly, K.R., Jost, R.M., Dao, L., Beauchamp, C.L., Leffler, J.N. and Birch, E.E., 2016. Binocular iPad game vs patching for treatment of amblyopia in children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA ophthalmology, 134(12), pp.1402-1408.