One thing I keep coming back to is this: children are often far more capable than we give them credit for. And yet, some schools continue to fill their days with worksheets. Often well-intentioned, yes. But let’s be honest — many of them are, if not actively soul-destroying, then at the very least designed to extinguish any flicker of genuine curiosity.

The trouble isn’t that worksheets exist. It’s that they’re frequently misused — becoming the learning rather than supporting it. There’s a world of difference between a worksheet used as part of a carefully scaffolded lesson and a worksheet slapped on the desk because Ofsted are visiting this year and your Deputy Head (Academic) has asked for ‘Evidence of Learning’ in the children’s books. In these scenarios, worksheets come back covered in diligent green pen and detailed feedback at the start of the year. By the end, it’s a smiley face stamp, and the faint outline of a coffee cup.

To be clear: in a gradual release model — “I do, we do, you do” — worksheets can serve a valuable role. They offer a structured way for children to practise something they’ve just been shown. They can help build fluency and confidence. No objection there.

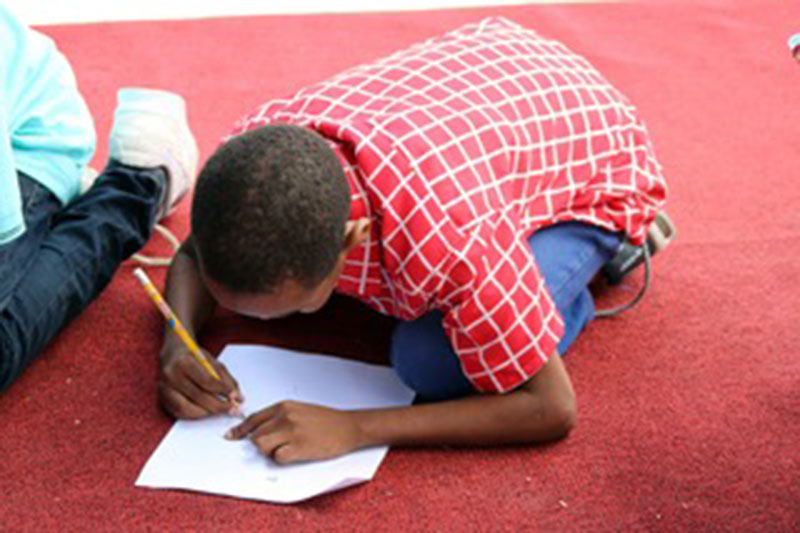

But when the worksheet becomes the end product of the lesson? That’s when we start running into problems. It signals, perhaps unintentionally, that we don’t believe children are capable of more — more complexity, more creativity, more independence. And frankly, they are.

Cognitive science tells us that motivation is not simply about reward or punishment — it’s about autonomy, purpose, and mastery. If we want children to retain what they’ve learned, we need to connect learning to something meaningful. That means asking for original thinking. Problem-solving. Application. Ideally, something with a real-world audience — not just a stack of papers returned with ticks and the occasional “well done.”

This is where schools who have embraced ‘project-based learning’ are blazing an interesting trail. They’ve done away with traditional worksheets in favour of interdisciplinary projects — where children publish books, design exhibitions, even pitch solutions to local issues. And here’s the thing: those children aren’t unicorns. They’re not magically more capable than ours. They’re just being treated as if they have something valuable to offer — and given the space to prove it.

None of this is to say we should torch the worksheet trolley and dance around the bonfire. But we should be asking: what’s the purpose of this activity? What cognitive challenge is it providing? Is it helping this child take the next step — or just keeping them busy?

Because children don’t need more filler. They need real thinking. Real problems. Real learning.

And ideally, slightly fewer worksheets with cartoon owls in the corner.